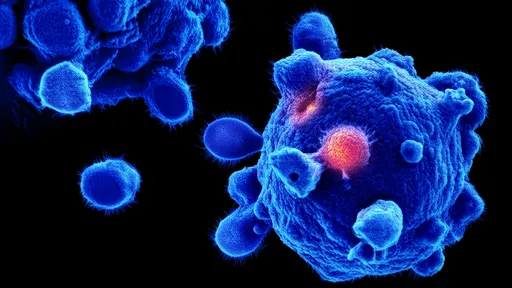

The birth of the world's first gene-edited babies in 2018 sent shockwaves through the scientific community and beyond. Chinese researcher He Jiankui's announcement that he had altered the DNA of twin girls to make them resistant to HIV crossed what many considered an ethical red line in genetic science. This unprecedented experiment ignited fierce debates about the moral boundaries of human genetic engineering and raised urgent questions about oversight in an era of rapidly advancing biotechnology.

The experiment focused on the CCR5 gene, which plays a crucial role in how HIV enters cells. Using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, He claimed to have successfully modified this gene in embryos that were then implanted and carried to term. While the scientific merits of his work were immediately questioned—both for its medical necessity and technical execution—the broader implications of his actions created a crisis in bioethics that continues to reverberate today.

What made this case particularly alarming was not just the technical achievement, but the deliberate flouting of established ethical norms. The research was conducted in secret, bypassing standard peer review processes and institutional oversight. The subjects—vulnerable couples where the father was HIV-positive—may not have fully understood the risks involved in this untested procedure. This breach of trust between researchers and participants represented a dangerous precedent that could undermine public confidence in legitimate medical research.

International reaction was swift and overwhelmingly negative. The World Health Organization called for stricter governance frameworks, while leading scientists condemned the experiment as irresponsible and premature. China's government launched an investigation that ultimately led to He's imprisonment for illegal medical practice. However, the genie was already out of the bottle—the technological capability to edit human embryos now existed, and others might be tempted to follow this controversial path.

The scientific community faces a dilemma. CRISPR and other gene-editing tools hold tremendous promise for treating genetic diseases, potentially eliminating conditions like sickle cell anemia or cystic fibrosis. Yet the same technology could be used for enhancement purposes—creating so-called "designer babies" with selected physical or cognitive traits. Without clear international standards, the potential for a new era of genetic inequality looms large, where only the wealthy can access genetic advantages for their children.

Ethicists warn that we're entering uncharted territory. The changes made to germline cells (sperm, eggs, embryos) are heritable, meaning they would be passed down to future generations. This raises profound questions about consent—how can future generations consent to alterations made before their birth? The long-term effects of such edits remain unknown, and unintended consequences might not appear for decades or generations.

In the aftermath of the scandal, many countries have moved to strengthen regulations governing human genome editing. Some have imposed moratoriums on germline editing, while others are developing more nuanced frameworks that allow research while prohibiting clinical applications. However, the global nature of science means that determined researchers can always seek out jurisdictions with weaker oversight—a phenomenon sometimes called "ethics tourism."

The case also highlighted the growing divide between scientific capability and societal readiness. While we can technically perform certain genetic modifications, we lack consensus on whether we should. Cultural differences in ethical perspectives further complicate international agreement. Some nations view genetic medicine more permissively, while others maintain strict prohibitions based on religious or philosophical objections to "playing God."

Looking ahead, the scientific community must grapple with difficult questions about equitable access to genetic technologies, appropriate oversight mechanisms, and the fundamental question of what it means to be human in an age where our biology might become as malleable as computer code. The birth of those first gene-edited babies may come to be seen as a turning point—the moment when humanity had to confront the awesome power and profound responsibility that comes with editing our own blueprint of life.

As research continues—in carefully controlled settings—the debate has shifted from whether we can edit human genes to how we should govern such powerful technology. The challenge now is to develop ethical frameworks that neither stifle potentially life-saving medical advances nor allow reckless experimentation that could harm individuals and destabilize societies. The story of gene-edited babies is ultimately a story about scientific ambition, ethical boundaries, and our collective vision for the future of humanity.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025